Current status of GI endoscopy in Thailand: it’s time to restart endoscopy during COVID-19 infection

Introduction

Endoscopy service in Thailand is currently facing a challenging situation, not only from the disproportionate ratio of patients to trained health care personnel, but the restrictions caused by the continued global spread of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) (1). With modern equipment, physician and staff training, and a growing number of experienced medical centers, Thailand has the opportunity to deliver a great deal of advanced endoscopy services including endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) and endoscopic ultrasonography (EUS). Endoscopic capacity has also increased in rural hospitals in remote regions of the country to reach previously underserved communities. Another big policy step by the government has been the commencement of a nationwide colon cancer screening campaign that started in 2017 (2,3). Unfortunately, services have been interrupted since the virus epidemic began. Endoscopy is characterized as an aerosol generating procedure and there have been shortages of personal protective equipment (PPEs) (4). The physical distancing policy, including periods of lockdown, state quarantines, and additional emergency declarations that have asked people to stay home have caused the delay or cancellation of many endoscopies.

Thai Association for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (TAGE)

On 20th October 2005, the TAGE was founded as a coalition among Gastroenterologists and Surgeons to provide leadership and guidance for both academic and health care service. The mission of our association specifically focuses on enhancing knowledge regarding all types of endoscopic procedures. We regularly organize meetings including live demonstrations, endoscopic challenges and therapeutic training for both domestic and international trainees and endoscopists. In addition to the benefits, we bring to our audiences, our faculty members often receive an invitation abroad to lecture or offer expertise in their fields. The association has also published guidelines and an endoscopy atlas book in the English and Thai language that is suitable for young endoscopists and GI endoscopy nurses/associates that can be downloaded for free from our website (http://www.thaitage.org/en/).

Colorectal cancer screening program

National colorectal cancer screening is a key TAGE objective that we are pleased to deliver to our citizens. With high demand but limited manpower, we have launched a screening campaign using first an immunochemical fecal occult blood test first (i-FOBT) and then followed up with a colonoscopy, performed in cases of positive i-FOBT. Due to the tremendous value and cost-effectiveness of this campaign, we have been successful in persuading all government health care systems including both universal coverage and social welfare funded-coverage to accept and reimburse for the cost of these screenings. For this policy success, we are greatly appreciative. Since additional screenings have caused increased workloads in rural areas of the country, we have set up endoscopy teams to assist colonoscopists in high demand areas to decrease waiting time for colonoscopy. Data from the screening program has been collected and systematically recorded in our planning efforts for a comprehensive nationwide surveillance initiative.

A nationwide Thailand colorectal cancer (CRC) screening program was launched in October 2017 and was estimated to screen about 13.3 million. A pilot implementation program using a cut-off fecal hemoglobin concentration of 200 ng/mL found that about 1.3 % had positive FIT and 72% of FIT-positive individuals eventually underwent colonoscopy (5). To date, the cutoff level of FIT for the program was 100 ng/mL which is approximated by 12 % of the screening population. However, there is increasing evidence that using the 25 ng/mL cutoff for high-risk patients and the 150 ng/mL cutoff for average-risk patients could maintain the sensitivity for CRC (80%) (3). Apart from that, clinical risk factors should also be considered together with fecal occult blood test (FOBT) results. Our data suggests that those with positive feal immunochemical test (FIT) results and high-risk scores should be prioritized for colonoscopy firstly (6). Although a reduction in CRC-related mortality has not been, our government has established a program for early CRC screening program named as one day surgery for both social welfare and universal coverage. With the COVID-19 pandemic, unfortunately, the screening program was postponed until a better situation.

COVID 19 infection and its impact

In Thailand, basic endoscopy services including esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) and colonoscopy are performed at nearly all provincial hospitals. Advanced endoscopies including ERCP, EUS and endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) are available only at selected university hospitals or tertiary care hospitals depending on equipment, human and financial resources. For training purposes, we expect that all of our fellows will achieve a high level of basic endoscopy training including diagnosis and therapeutic EGD and colonoscopy. Our faculties are working to create an awareness of all the new techniques such as image enhanced endoscopy and new techniques for difficult polypectomies. Currently, fellows who have an interest in advanced endoscopy, spend 1 more year to have additional training but the training has not been officially approved by the TAGE yet. We are planning to approve a standard curriculum of advanced, 1-year endoscopy courses. Due to COVID-19, implementation of this official approval is temporarily delayed.

COVID-19 infection and its effect on training services

Our trainees have suffered significantly from the COVID-19 situation. Normally, they would be practicing under supervision for 2 years as a GI fellow where they can gain competence as a gastroenterologist both in terms of knowledge and procedure. They have the opportunity with a consent to treat to begin performing procedures for patients. Due to the COVID-19 situation, the GI fellows have fewer chances to practice and gain knowledge which might make them less confident and decrease their morale. With the COVID-19 pandemic, the number of procedures were decreased and made our fellow less involved with multiple reasons. Although this data in our country is still scarce, many training centers conduct hands-on models including training models by manufacturer, pig-stomach model and varices training model.

COVID-19 infection and its effect on our endoscopy service

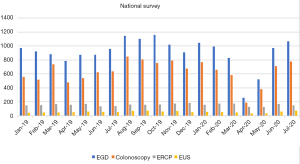

The spreading of the corona virus continues to bring much negative impact. Not only do upper endoscopy procedures generate many aerosol particles, but reports indicate that lower endoscopy can also expose treatment staff to a number of viral particles. Most of the guidelines have recommended postponing all elective procedures to avoid spreading through this route. Thailand first detected the COVID-19 infection in January 2020 and immediately alerted health care professionals to be aware of this virus. With strict screening at our countries’ airports and borders, the number of confirmed cases grew only slowly in the first two months. Nevertheless, with the highly contagious nature of the virus and the overcrowded activities of people, the number of new cases jumped to 1,609 cases by March 2020. Our government then declared a state of emergency and enforced a lock down beginning at the end of March. In addition, a 14-day state quarantine was adopted in early April for all foreign tourists and Thai nationals entering the country who were returning from abroad. Although the incidence of new COVID-19 cases in April 2020 stood at approximately 1,300 cases, it still represented a decrease from the previous month. For the next three months, new case incidence fell sharply to around 100 per month (Figure 1).

On behalf of the Thai Association of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (TAGE), we introduced guidelines to support all endoscopists practicing in Thailand (7,8). Regarding the dynamic incidence rates of infection, we first advised all units to check the risk status of patients and offered a blueprint for appropriate self-personal protective equipment. Moreover, we recommended that our endoscopists perform only emergency cases and postpone all elective procedures until the situation is better resolved. With the difficult times in March and April 2020, the number of EGD and colonoscopy cases dropped significantly. Regarding the non-medical aspect, the situation also caused negative outcomes for persons seeking medical care. For example, the city lockdown and other restrictive transport policies prevented patients and their relatives from travelling across provinces. Combined with the problems mentioned above, some procedures were only performed at a few hospitals in limited geographic areas. The situation caused many patients to lose their chance to access medical care or to undergo low-risk procedures which reduce quality of life such as percutaneous transhepatic biliary drainage (PTBD) instead of an endoscopically biliary drainage.

Unpublished data from the TAGE clearly show that the total number of all procedures dramatically decreased to less than 10% of normal activity, indicating that only emergency procedures were being performed. Nevertheless, the number of ERCP and EUS cases remained almost stable during this whole time period. It might be said that the nature of these two procedures is standard for all therapeutic purposes. For all of these reasons, we believe that these therapeutic and beneficial procedures needed to be completed for the patients. We were lucky that it did not cause any further spreading of the virus.

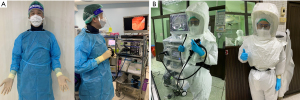

It is believed that COVID-19 testing before procedures has helped protect health care workers and prevented viral transmission in hospitals which can be one of the riskiest places. At the beginning of the COVID-19 situation, our health ministry introduced policies in the early weeks and months and continued to collect surveillance data. In hindsight, it might be concluded that this policy might not be working in our country due to the low incidence rate and lack of cost-effective testing accuracy. There are recommended PPE by TAGE published last year which might be one reason that gives confidence to our endoscopist (Figures 2,3).

Reopening Thailand and our viewpoint

In November 2020, we were at a point where the number of in-country infections remained essentially zero in contrast to most other countries in the world. Most of the positive tests were coming from the state quarantine which included returning Thai nationals and a limited number of expats who were legally allowed to return due to family or work. Data from the Ministry of Health stated that the risk of COVID-19 Infection was nearly zero. Consequently, we gave endoscopy services the opportunity to reopen at this time with confidence and caution. Although the new normal trend of endoscopy services brings with it some difficulties that may stay for a while, it could turn out to be sufficient and simple enough to have the endoscopy room staff manage only screen risk and respiratory symptoms before the patient comes to the operating room. We did not, however, recommend COVID-19 testing before undergoing procedures. With a relatively low incidence and a problem of false positive tests, asymptomatic patients who test positive might not be infected. A false positive would make for an uncomfortable situation between the patient and their family and the endoscopy staff. Refusal to treat becomes even more difficult when their illness has reached an emergency or urgency level that requires endoscopy not to be delayed.

Although our country is now experiencing a new phase of COVID-19 infection since December 2020, the daily number of new cases remains low, at about 200 to 300 cases per day in a country of nearly 70 million. The nation’s COVID prevention policies seem to be working in terms of slowing the spread without too much additional disturbance to the economy. Thailand’s important tourist sector continues to suffer greatly like most global resort areas.

Surveillance data has shown that most of the COVID cluster is coming from illegal and crowded activities, a large proportion of them migrant workers, as well as from the initial area of the outbreak in Samut Sakhon. Few if any patients have intersected with these clusters. The light at the end of this pandemic might be vaccines that are not too far off in the future with the government proposing to begin in March/April 2021. To fully re-open our endoscopy services with safety, vaccines should be available and distributed systematically. Prioritization is the keyword for success in this campaign. Endoscopy staff must be considered as frontline healthcare workers, and should not experience delays in receiving vaccinations, since they handle emergency cases such as gastrointestinal hemorrhage, cholangitis, and cancer. Similar to health care workers (HCWs), some patients should also receive vaccination prioritization. We have proposed that patients with comorbidities like cancer should be prioritized for vaccination. At the same time, endoscopy service should not be postponed due to a lack of vaccine availability. When local capacity for vaccination allows, consideration should be given to provide urgent vaccination for patients in additional lower, but still at-risk vaccination priority groups including those treated for variceal bleeding under banding program, moderate to severe Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) cases, recently diagnosed cancer patients, and time-sensitive conditions which might be led to significant complications.

Hopefully, 2021 will be the year where we can bring in new sunshine in terms of a work-life balance, sustainability of endoscopy services, and cutting-edge research. The number of measures that are currently being taken should allow the safe resumption of limited gastrointestinal endoscopic services during the virus deceleration period and the early recovery phases of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Acknowledgments

Authors thank the research team of the Department of Medicine, Faculty of Medicine, Chulalongkorn University for final editing of the manuscript.

Funding: This study was supported by Pancreas Research Unit, Department of Medicine, Faculty of Medicine, Chulalongkorn University.

Footnote

Conflicts of Interest: Both authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at https://dx.doi.org/10.21037/dmr-21-11). KH is currently a member of TAGE and PK was former president of TAGE (2018-2020). The authors have no other conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- Rerknimitr R, Akaraviputh T, Ratanachu-Ek T, et al. Current Status of GI Endoscopy in Thailand and Thai Association of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (TAGE). Siriraj Med J 2018;70:476-8.

- Najib Azmi A, Khor CJL, Ho KY, et al. Endoscopic Submucosal Dissection Outcomes for Gastroesophageal Tumors in Low Volume Units: A Multicenter Survey. Diagn Ther Endosc 2016;2016:5670564. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Aniwan S, Ratanachu-Ek T, Pongprasobchai S, et al. Impact of Fecal Hb Levels on Advanced Neoplasia Detection and the Diagnostic Miss Rate For Colorectal Cancer Screening in High-Risk vs. Average-Risk Subjects: a Multi-Center Study. Clin Transl Gastroenterol 2017;8:e113. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Chiu PWY, Ng SC, Inoue H, et al. Practice of endoscopy during COVID-19 pandemic: position statements of the Asian Pacific Society for Digestive Endoscopy (APSDE-COVID statements). Gut 2020;69:991-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Khuhaprema T, Sangrajrang S, Lalitwongsa S, et al. Organised colorectal cancer screening in Lampang Province, Thailand: preliminary results from a pilot implementation programme. BMJ Open 2014;4:e003671. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Aniwan S, Rerknimitr R, Kongkam P, et al. A combination of clinical risk stratification and fecal immunochemical test results to prioritize colonoscopy screening in asymptomatic participants. Gastrointest Endosc 2015;81:719-27. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kongkam P, Tiankanon K, Ratanalert S. The Practice of Endoscopy during the COVID-19 Pandemic: Recommendations from the Thai Association for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (TAGE) In collaboration with the Endoscopy Nurse Society (Thailand). Siriraj Med J 2020;72:283-6. [Crossref]

- Rerknimitr R, Soetikno R, Ratanachu-Ek T, et al. Additional measures for bedside endoscope cleaning to prevent contaminated splash during COVID-19 pandemic. Endoscopy 2020;52:706-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

Cite this article as: Harinwan K, Kongkam P. Current status of GI endoscopy in Thailand: it’s time to restart endoscopy during COVID-19 infection. Dig Med Res 2021;4:67.