Gastrointestinal hemorrhage from a duodenal varix rupture: a case report

Introduction

Duodenal varices (DV) are part of ectopic varices (EcV), defined as dilated splanchnic (mesoportal) veins/varicosities and/or portosystemic collaterals in the gastrointestinal tract except the gastroesophageal region (1). They account for up to 17% of the EcV and are seldomly seen as prevalence is reported between 0.2–0.4% in all patients undergoing upper endoscopy (2,3). DV are predominantly found in the duodenal bulb and second part of the duodenum as their frequency declines further distally (4). EcV function as natural portosystemic shunts and most patients have portal hypertension (PHT) (intra- or extrahepatic) with liver cirrhosis accounting for 30% of the patients with DV (5). However, EcV can form in the absence of PHT as described in abdominal trauma, tumours, vascular anomalies and thrombotic disorders (Table 1) (6,7).

Table 1

| Etiology of duodenal varices in world literature |

| Cirrhosis of the liver |

| Hepatocellular carcinoma |

| Hepatic vein thrombosis (e.g., Budd-Chiari syndrome) |

| Inflammatory process (pancreatitis, cholangitis) |

| Klippel-Trenaunay-Weber syndrome |

| Schistosomiasis |

| Surgical Procedures (OG varices band ligation) |

| Tumour (pancreas, periportal) |

| Thrombotic disorders and Coagulopathies |

| Trauma |

| Vascular anomalies |

Bleeding from EcV accounts for 2–5% of all gastrointestinal tract bleeding (8). The majority of these EcV bleeding is caused by peristomal (26%), duodenal (17%) and small intestinal (17%) varices (9,10). When bleeding from DV occurs, mortality is reported as high as 40% (11). Management guidelines on ectopic (and duodenal) variceal bleeding are still lacking although various options are available. Classic, invasive surgical approaches (ligation, duodenectomy, open shunt surgery) have been largely replaced by endoscopic (banding, sclerotherapy) procedures, especially in the acute setting. In a later stage, treatment is aimed at lowering the venous pressure and therefore avoiding bleeding episodes and the formation of new varices. Open shunt surgery remains a viable option although more recent radiological interventions like Transjugular Intrahepatic Portosystemic Shunt (TIPS) or Balloon-occluded Anterograde/Retrograde Transvenous Obliteration (BATO/BRTO) show good results. This case report describes a patient with active bleeding from DV located in the distal part of the duodenum and we continue to discuss the diagnostics, treatment and etiology of DV. We present the following article in accordance with the CARE reporting checklist (available at http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/dmr-20-86).

Case presentation

A 77-year-old male presented after having a sudden onset, russet diarrhoea that was preceded by an episode of heavy sweating. Symptoms started the night before and continued through the morning of admission. His medical history showed superior mesenteric vein thrombosis, diagnosed eight years prior to presentation, possibly due to a suspected antithrombin-III deficiency (Factor V Leiden and JAK2 mutation analysis both negative) for which he received anticoagulants in the six months following diagnosis. At the time of presentation, he was no longer on anticoagulants neither was the diagnosis of antithrombin-III deficiency confirmed later on. Other relevant history consisted of oesophagitis grade A, duodenal ulcer and hereditary hemochromatosis (adult type, HFE-gene related, homozygous mutation).

At first, clinical investigations showed a pale man with normal vital signs (blood pressure 125/74 mmHg, heart rate 80/min, respiratory rate 14/min). Digital rectal examination was normal except for melena. Blood results showed a slight anaemia (haemoglobin 9.8 g/dL, haematocrit 30.1%) and a shortened APTT of 23.5 s. All other results were within normal range. An immediate esophagogastro-duodenoscopy could not identify any protruding varices, bleeding sites, blood clots or other abnormalities. The endoscopy report states introduction up to the third part of the duodenum.

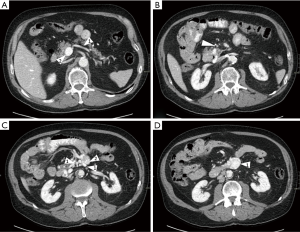

For further evaluation of bleeding sites, urgent CT-angiography was performed and revealed a contrast blush out of a varix that protruded into the lumen of duodenum part 3 (Figure 1). Further, extensive varicose veins were seen at the transition of duodenal parts 3-4 and a near occlusion of the superior mesenteric vein (due to earlier thrombosis).

During the following hours, the patient became increasingly haemodynamic instable and developed hematemesis. He underwent emergency laparotomy. Duodenotomy showed three protruding veins, one of which was actively bleeding. These were ligated after which the patient stabilised. After three days on intensive care, non-ventilated, and 7 days on a conventional ward, he was discharged. Three months later, the patient underwent a selective endovenous embolization of the DV with cyanoacrylate (Glubran®, 3×1 mL). After initial surgery, the only temporary complaint of the treatment received was a prolonged loss of appetite. The possible complications of selective DV embolization are shown in Table 2. Lifelong anticoagulation therapy was started (warfarin, target INR 2-3) as our patient was in a hypercoagulable state due to his antithrombin III deficiency.

Table 2

| Complications of selective duodenal variceal embolization |

| Minor complications |

| • Abominal pain or fever |

| • Extravasation of the embolization agent with local reaction |

| • Variceal rupture (without hemodynamic instability) |

| • prolonged bleeding at puncture sites and/or hematoma |

| Major complications |

| • Those requiring an increased level of medical care, including reactions to ethanolamine oleate |

| • conversion to surgery |

| • prolonged hospital stay |

| • Any event related to the procedure that produced hemodynamic instability) |

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee(s) and with the Declaration of Helsinki (as revised in 2013).

Discussion

Due to their low prevalence, the diagnosis and management of DV remains challenging and most of the literature consists of case reports and small population studies.

Possible etiology of DV are shown in Table 1 (6,7). As previously noted, DV function as portosystemic shunts to relieve PHT that is present in a majority of the cases. This is defined as a hepatic pressure venous gradient (HPVG) above 5 mmHg, although complications usually develop above the 10–12 mmHg threshold (13). DV are more frequently seen in the duodenal bulb and second part of the duodenum with their frequency declining distally (2,4). Anatomy and its variations in EcV have been extensively described by Sharma et al. (14). Although rare, in this case the left gonadal vein also drains the third and fourth part of the duodenum (14,15).

The diagnosis is often made during endoscopy for upper GI-tract bleeding. However, like in our case, a lack of visualisation of the culprit vein due to food remnants, duodenal folds, extensive clothing/bleeding or endoscopy in a non-bleeding interval are among the diagnostic challenges. Furthermore, it is the authors believe that, due to the low prevalence, insufficient awareness of the existence of EcV in the distal duodenum D3-4 might also contribute to a lower detection rate. Early diagnosis in high-risk patients (any form of PHT or previous endoscopic sclerotherapy procedures for gastro-intestinal varices) can be enhanced by screening, like in patients with liver cirrhosis, and by performing a full endoscopic inspection of the entire duodenum, including D3 and D4 (16). The benefit of performing an endoscopy is that it allows the operator to simultaneously diagnose and try to control the bleeding with clipping, ligation or sclerotherapy, albeit at a high rate of re-bleeding and ulcers (17). Iqbal et al. report a case of fatal GI bleeding after failed attempts to clip the culprit vessel (18). Because of these difficulties, an accurate diagnosis might be delayed or even missed. Therefore, contrast enhanced imaging like MRI/CT can be of assistance not only in identifying the focus of bleeding but also a possible underlying diagnosis (cirrhosis or splanchnic vein thrombosis) and guide following therapies (15).

Therapeutic options are plenty: endoscopy (clipping, ligation, sclerotherapy), interventional radiology (TIPS and BRTO or BATO, depending on the approach) and surgical interventions (duodenectomy, venous ligation, open shunt surgery) are used. First and most important is to correctly assess the level of hemodynamic instability and whether there is sufficient time to allow for a minimally invasive endoscopic intervention. Swift decision making is crucial and one should not hesitate to proceed to invasive surgery. Whilst TIPS and BRTO/BATO have a favourable outcome in gastric varices, both techniques have a high re-bleeding rate in EcV (1,19). Therefore, TIPS is a mainly to be considered a first-line therapy for bridging towards transplantation or for those patients unfit for surgery. Procedural risk and underlying etiology should be taken into account individually. BRTO/BATO are valid options in patients who are unfit for surgery or failed endoscopy, especially in those with existing hepatic encephalopathy (19,20). The complexity of the procedure and lack of expertise limits its global use with successful reports mainly originating from Japan (20). Open surgery (ligation, duodenectomy or open shunt surgery) has been used with success and proves vital in patients with bowel ischemia and extensive peritonitis (21). High volume studies on the outcome of open surgery are still lacking. Salzedas-Netto et al. presented a case with a modified meso-Rex shunt, using the internal jugular vein as a conduit between the splenic and the left portal vein (22). The use of this technique is however, limited to extrahepatic portal/splanchnic vein obstruction.

Conclusions

We presented a case of a distal DV bleeding that was successfully managed with surgical ligation and, in a later phase, sclerotherapy. Our case is unique because there was no underlying liver pathology and formation of venous collaterals, at the level of D3/D4, was based on earlier SMV obstruction due to superior mesenteric vein thrombosis. As bleeding from DV is seldomly seen, diagnosis of a more distal DV in a patient without liver cirrhosis or PHT is even more challenging. Endoscopy plays a pivotal role in the diagnosis and acute management of DV and should be carried out with the possibility of more distal DV in mind. We advise that urgent endoscopic interventions are to be carried out by experienced clinicians as this might avoid open surgery. Guidelines, meta-analyses and high-quality reviews that compare different therapies are still lacking and therefore further research is necessary.

Acknowledgments

Funding: None.

Footnote

Reporting Checklist: The authors have completed the CARE reporting checklist. Available at http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/dmr-20-86

Peer Review File: Available at http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/dmr-20-86

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/dmr-20-86). MDM serves as the unpaid editorial board member of Digestive Medicine Research from April 2020 to March 2022. The other authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee(s) and with the Declaration of Helsinki (as revised in 2013). Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this Case report and any accompanying images.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- Saad WE, Lippert A, Saad NE, et al. Ectopic varices: anatomical classification, hemodynamic classification, and hemodynamic-based management. Tech Vasc Interv Radiol 2013;16:158-75. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hashizume M, Tanoue K, Ohta M, et al. Vascular anatomy of duodenal varices: angiographic and histopathological assessments. Am J Gastroenterol 1993;88:1942-5. [PubMed]

- Al-Mofarreh M, Al-Moagel-Alfarag M, Ashoor T, et al. Duodenal varices. Report of 13 cases. Z Gastroenterol 1986;24:673-80. [PubMed]

- Tanaka T, Kato K, Taniguchi T, et al. A case of ruptured duodenal varices and review of the literature. Jpn J Surg 1988;18:595-600. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sato T, Akaike J, Toyota J, et al. Clinicopathological features and treatment of ectopic varices with portal hypertension. Int J Hepatol 2011;2011:960720. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bommana V, Shah P, Kometa M, et al. A Case of Isolated Duodenal Varices Secondary to Chronic Pancreatitis with Review of Literature. Gastroenterology Res 2010;3:281-6. [PubMed]

- Bhagani S, Winters C, Moreea S. Duodenal variceal bleed: an unusual cause of upper gastrointestinal bleed and a difficult diagnosis to make. BMJ Case Rep 2017;2017:bcr2016218669. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Larson JV, Steensma EA, Burke LH, et al. Fatal upper gastrointestinal bleed arising from duodenal varices secondary to undiagnosed portal hypertension. BMJ Case Rep 2013;2013:bcr2013200194. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Helmy A, Al Kahtani K, Al Fadda M. Updates in the pathogenesis, diagnosis and management of ectopic varices. Hepatol Int 2008;2:322-34. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Malik A, Junglee N, Khan A, et al. Duodenal varices successfully treated with cyanoacrylate injection therapy. BMJ Case Rep 2011;2011:bcr0220113913. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Khouqeer F, Morrow C, Jordan P. Duodenal varices as a cause of massive upper gastrointestinal bleeding. Surgery 1987;102:548-52. [PubMed]

- Zamora CA, Sugimoto K, Tsurusaki M, et al. Endovascular obliteration of bleeding duodenal varices in patients with liver cirrhosis. Eur Radiol 2006;16:73-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Vizzutti F, Schepis F, Arena U, et al. Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS): current indications and strategies to improve the outcomes. Intern Emerg Med 2020;15:37-48. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sharma M, Rameshbabu CS. Collateral pathways in portal hypertension. J Clin Exp Hepatol 2012;2:338-52. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bhat AP, Davis RM, Bryan WD. A rare case of bleeding duodenal varices from superior mesenteric vein obstruction -treated with transhepatic recanalization and stent placement. Indian J Radiol Imaging 2019;29:313-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Jakab SS, Garcia-Tsao G. Screening and Surveillance of Varices in Patients With Cirrhosis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2019;17:26-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Jonnalagadda SS, Quiason S, Smith OJ. Successful therapy of bleeding duodenal varices by TIPS after failure of sclerotherapy. Am J Gastroenterol 1998;93:272-4. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Iqbal S, Likhtshteyn M, O'Brien D, et al. Duodenal Varix Rupture - A Rare Cause of Fatal Gastrointestinal Hemorrhage: A Case Report and Review of Literature. Am J Med Case Rep 2019;7:62-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Mukund A, Deogaonkar G, Rajesh S, et al. Safety and Efficacy of Sodium Tetradecyl Sulfate and Lipiodol Foam in Balloon-Occluded Retrograde Transvenous Obliteration (BRTO) for Large Porto-Systemic Shunts. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol 2017;40:1010-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- de Franchis R, Baveno VIF. Expanding consensus in portal hypertension: Report of the Baveno VI Consensus Workshop: Stratifying risk and individualizing care for portal hypertension. J Hepatol 2015;63:743-52. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Rajesh S, Mukund A, Arora A. Imaging Diagnosis of Splanchnic Venous Thrombosis. Gastroenterol Res Pract 2015;2015:101029. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Salzedas-Netto AA, Duarte AA, Linhares MM, et al. Variation of the Rex shunt for treating concurrent obstruction of the portal and superior mesenteric veins. J Pediatr Surg 2011;46:2018-20. [Crossref] [PubMed]

Cite this article as: Dries P, de Maat M, De Schepper B, D’Archambeau O, Hubens G, Beunis A. Gastrointestinal hemorrhage from a duodenal varix rupture: a case report. Dig Med Res 2020;3:70.