胃食管反流病的创新治疗——胃底折叠术、磁铁装置及内镜治疗

引言

胃食管反流病(gastroesophageal reflux disease, GERD)是一种多因素、慢性、易复发疾病,定义为胃内容物反流至食管,是西方最常见的消化系统疾病[1,2]。人群患病率达20%,以30-60岁为高峰,通常表现为间歇性烧心或反流[1,3]。但是,也有患者表现为不典型症状如胸痛、慢性咳嗽。GERD的并发症在男性及老年患者中更为常见,如食管炎、巴雷特食管、狭窄[1]。

为缓解症状、预防并发症,质子泵抑制剂(proton pump inhibitors, PPIs)一直是GERD的主要治疗方式。然而,仍有许多患者症状无法完全缓解或出现明显的不良反应,因此需要替代的治疗手段。此外,每年用于GERD治疗的直接费用估计达到100亿美元,这也是一项亟待解决的重要问题[4]。腹腔镜抗反流术(laparoscopic anti-reflux surgery, LARS)作为难治性GERD的一线治疗手段,已在多项研究中证实其与PPIs同样有效[5]。LARS同样存在一些风险,因此更加微创的治疗技术逐渐走向前台,包括增强食管下括约肌(lower esophageal sphincter, LES)压力的磁铁装置以及一系列内镜治疗技术如LES射频消融术、经口无切口胃底折叠术(transoral incisionless fundoplication, TIF)、抗反流黏膜切除术(anti-reflux mucosectomy, AMRS)[6]。本综述旨在总结GERD治疗技术的发展,重点阐述新的技术进展及其安全性。

病理生理

虽然一定程度、短时间的胃内容物反流可能是正常的,但通常可以被抗反流屏障,即LES与膈肌脚组成的高压区所阻断[7]。其相当于一个瓣阀,由His角向腔内延伸而成并通过膈食管韧带、胃贲门肌纤维来维持其解剖学位置,使得上述两个结构重叠[7,8]。一旦有害刺激超过了食管黏膜屏障所能耐受的阈值,则会形成病理性的GERD[7]。虽然并不一定会观察到黏膜损伤,但抗反流屏障已经受损[1,7]。GERD的病因是多方面的,大致分为结构/解剖改变、饮食及生活方式或功能性。肥胖、怀孕、长时间仰卧位、酒精、辛辣食物等均可增加GERD的发病风险。功能性问题包括食管蠕动不足致食物清除功能下降、低静息压、胃扩张后瞬时LES松弛[5]。另一方面,结构性问题也可使抗反流屏障受损,主要见于His角消失导致的LES压力区改变,通常与食管裂孔疝(hiatal hernia, HH)有关[1,9]。

临床表现及诊断

大多数GERD患者伴有典型症状,包括烧心、反流、胸痛、吞咽困难,通过饮食、生活方式调节、PPIs进行治疗[10]。值得重视的是,GERD也可表现为非典型症状,如胸痛合并偶发哮喘、吸入性肺炎、肺损伤[10,11]。一些病程长的患者还可能会出现体重减轻、吞咽困难等报警症状[1]。

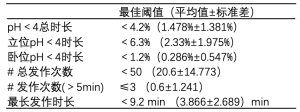

虽然病史采集是GERD诊断的关键,但体格检查往往正常,且症状多为非特异性[12]。因此,往往需要多种辅助检查进一步评估功能与结构情况。Jobe等在共识指出,这些检查对于客观评估症状及制定治疗方案至关重要[12]。24 h食管pH监测是最常见的诊断工具,同时也是金标准,可记录远端食管的酸暴露,评估其与患者症状的关联性[13]。然后计算DeMeester综合评分以反映GERD的严重程度,若评分>14.72则视为远端食管酸暴露时间延长。DeMeester评分的原始内容见表1[14]。表格中列出了诊断的最佳阈值,其来源于一篇里程碑式的文章。需要重视的是,随着近来更大规模研究的开展,部分值已发生变化。此外,原始DeMeester评分使用的最佳值,较对照组的平均值高上2个标准差(standard deviations,SD)[14]。

胃镜也是一种有用的辅助检查,可直视评估食管黏膜情况,通常是诊断GERD的首要检查,但半数经pH监测证实为GERD的患者可无黏膜损伤[11]。食管造影可助于鉴别结构异常,如HH、狭窄、食管短缩,尽管胃镜是首选检查[10]。最后,食管高分辨率测压可以辅助诊断引起慢性GERD的食管动力障碍[10]。

治疗方法

GERD的起始治疗包括生活方式调整(饮食、运动)、抑酸药物,包括PPIs、H2受体阻滞剂,以及抗酸剂[1]。许多患者(高达40%)即使经过以上治疗仍然无法实现完全缓解,因此需要其他手段干预以缓解、控制症状[15]。这些干预也适用于服用PPIs出现严重不良反应或不希望终生服药的患者[1]。无论治疗方式如何,最终目标是一致的,即缓解症状、黏膜愈合、维持缓解、预防并发症。

药物治疗

GERD的治疗从生活方式调整开始,比如不吃某些食物(酸性食物、碳酸饮料)、不睡前进食、抬高床头、戒烟戒酒、减肥[16]。经以上方式干预,GERD症状若仍持续,则通常需要开始药物治疗,主要包括两类:酸中和药物(抗酸剂)、抑酸剂(PPIs、H2受体阻滞剂)[17]。虽然抗酸剂可缓解轻微症状,但在美国,自1989年以来,PPIs一直是治疗典型GERD症状的主要药物[1]。PPIs阻断了产酸的最终共同通路,因此在控制症状及缓解食管炎方面较H2受体阻滞剂更加有效[17]。值得注意的是,若增加药量后,症状仍不缓解,需要在治疗后半年进行胃镜检查以评估是否存在解剖学异常[12]。PPIs虽然十分有效,但也存在一些缺点,比如无法解决抗反流屏障的功能不全,许多患者需要不断增加药量和长期服药,因此认识到长期用药存在的风险是很重要的。PPIs有一些不良反应,包括停药后反弹性泌酸增多、骨折、低镁血症、营养吸收不良、某些感染易感性增加、慢性高胃泌素血症。慢性高胃泌素血症可能会增加胃癌发生风险,导致维生素B12的缺乏[18]。有趣的是,自PPIs应用以来,食管癌的发病率上升了,有一项研究显示两者间存在相关性[19]。虽然有待进一步研究阐释其机制,但不管怎样,长期使用PPIs始终困扰着GERD患者。因此,一些患者希望通过外科手术实现GERD的长期有效控制。

抗反流手术

1955年,Rudolf Nissen为一名反流性食管炎患者完成了首例胃底折叠术,并于1956年正式发表[20,21]。手术包括结扎胃短血管以及将胃底包绕下段食管360°[21]。这项开创性手术起初获得了成功并得到广泛应用,但之后由于并发症发生率高,开展数量明显下降[21,22]。此外,随着上世纪80年代PPIs的出现,进一步降低人们对这一开放性手术的兴趣[22]。供作参考,自1977年短松Nissen术开始应用,上世纪80年代的抗反流手术并发症发生率约在12%[23]。因此,只有那些药物治疗症状改善不佳或者严重食管炎的患者才会考虑采取传统的开放手术[22,23]。

1987年,Philippe Mouret在法国里昂完成了首例腹腔镜胆囊切除术,伴随腹腔镜技术的不断发展,GERD的手术治疗也发生了剧变[24]。1991年,Dallemagne等报道了腹腔镜Nissen胃底折叠术(laparoscopic Nissen fundoplication,LNF)的初步经验,患者术后症状得到明显改善,且未出现死亡病例[19-23]。有其他学者发现,与开放手术相比,包含LNF及部分包绕的LARS显著降低了手术并发症发生率及死亡率,且术后恢复更快[22-25]。因此,LARS已成为合并GERD并发症如狭窄、巴雷特食管、溃疡伴出血、年轻患者的理想手术方式,可能更加经济有效[21,24]。虽然Dallemagne等人的早期研究中未出现死亡病例,但值得注意的是,该手术也可发生严重并发症,甚至死亡。Galmiche等人开展的LOTUS研究显示,LARS组患者需住院并发症发生率为3%,严重不良事件发生率达26.8%[26]。此外,该研究还显示,5年期间里LARS组分别有11%、40%、57%出现吞咽困难、腹胀、胀气(P<0.001)[26]。

回顾历史,困扰术者的并发症在于膈肌脚关闭不全,胃在包绕下方滑动,进而疝入胸腔,使得修补失败致GERD复发,若包绕过紧或过长,则又可导致严重吞咽困难[22-25]。因此,尽管LARS具有不错的疗效,但确实存在一定风险,因此值得对多项比较LARS与PPIs优劣性的研究进行深入了解(表2)。对LARS研究的额外总结见附录1。

Full table

内镜治疗

内镜治疗为GERD患者提供了很好的替代选择。适应证的选择十分重要,因其决定了内镜治疗的有效性。对于药物治疗不佳、不愿长期服用药物、不希望外科手术的患者而言,内镜治疗创伤小且有效。术前胃镜检查是必要的,以评估患者是否适合内镜治疗。理想的适应证为HH≤2 cm,或Hill分级I-II级[37,38]。适用人群为存在药物禁忌、不愿或有外科手术禁忌的患者。相对禁忌证为体重指数(body mass index,BMI)>35 kg/m2、HH>5 cm、门静脉高压、胃瘫、巴雷特食管、怀孕、活动性溃疡[30]。此外,对于一些HH已被修复或者合并胃瘫、巴雷特食管但可以正规监测和治疗的患者,也可以接受内镜治疗。经报道并证实有效的内镜治疗方式有多种,以下介绍四种最为常用的(表2)。

射频消融

StrettaTM(Restech, Houston, TX)通过释放热射频能量作用于LES实现治疗,但确切机制尚不清楚。一种理论认为,射频可降低瞬时LES松弛的频率。也有理论认为,可能与胃食管结合部(gastro-esophageal juncture,GEJ)的组织顺应性降低、抗张强度增加、组织重塑有关。该系统包括射频发生器和导管,后者含有一个球囊及四个镍钛合金针状电极(22-g,5.5 mm)。操作时,首先胃镜定位并测量至齿状线(squamocolumnar junction,SCJ)的距离。然后置入导丝,将导管送至齿状线近端1cm。随后向球囊充气,使得四枚针状电极插入GEJ的肌层。施加能量1min,与此同时,不断用水冲洗以防止黏膜热损伤,并持续监测阻力以保证治疗有效。一次操作完成后,收回电极,缩回球囊。将导管旋转45°后,再次扩张球囊,释放电极,在每一水平面共完成8次操作。能量释放于3个水平面:SCJ近端0.5 cm、SCJ、SCJ远端0.5 cm。导丝撤回后,将球囊充气至25 ml后向外拉,直至其紧贴食管裂孔,然后再释放电极,施加能量1 min。之后收回电极,球囊放气,将导管旋转30°,在同一水平层面共完成12次操作。最后,将球囊推入胃内,扩张至22 ml,回拉至合适再进行同样的治疗操作。所有操作完成后,取出导管,再次胃镜检查以评估治疗是否充分[28,29,39-41]。

多项研究探索了StrettaTM的安全性及有效性(表2)。在一项开放标签多中心研究中,118例行StrettaTM治疗的患者,其中10例(8.6%)出现自限性并发症。1年后,患者GERD相关生活质量(GERD-health-related quality of life,GERD-HRQL)评分提高,酸暴露时间显著减少(P=0.0001)。此外,需要继续服用PPIs的患者仅有30%,而在基线时为88%(P<0.0001)[28]。

Noar等人报道了射频消融治疗的长期效果,研究入组217例难治性GERD患者,治疗后随访长达10年(最终纳入99例患者)。结果显示,41%(N=41)患者可完全停用PPIs,64%患者可将药量减半,72%患者GERD-HRQL改善。研究中发现,常见的不良反应包括胸部不适(50%)、消化不良(25%)、腹痛(8.3%)[29]。

Perry等人的一项meta分析纳入了18项研究,包含1441例患者,显示射频消融治疗后,GERD-HRQL(P=0.001)及酸暴露(P=0.007)均显著改善。最常见的并发症为食管溃疡、胃瘫[40]。近期的一项meta分析纳入28项研究、包含2468例患者,得到了类似结果,基线时需服用PPIs的患者在随访时仅有49%仍然需要。此外,食管酸暴露平均减少3.01(-3.72,-2.30,随机效应模型,P<0.001)[41]。

TIF

TIF已成为一种新兴的内镜治疗方式,通过重建抗反流屏障来治疗GERD。其可在内镜下加强His角,强化套索纤维,重建瓣阀机制。EsophyXTM(EndoGastric Solutions, Redmond, WA)是一种借由软式内镜完成操作的装置。内镜进入胃内后,倒镜并调整方向,使胃小弯、大弯侧分别位于12点、6点方向。将组织卷起并锁定于螺旋牵引器上,同时镜下吸气以确保胃底折叠在食管上。将装置调整至合适位置后,将H型聚丙烯扣件释放以重建一个新的GEJ。分别于前位、后位、长轴位进行操作从而建立一个5 cm长、300°的胃底折叠[42]。该术式与LARS类似,目标是建立至少2-4 cm、至少270°的胃底折叠。

一些研究显示,即使是在TIF的术后10年,其治疗效果仍然很好(表2)。Chang等进行的一项多中心前瞻性研究发现,TIF治疗组患者中,80%可在治疗半年后停用PPIs。此外,73%的患者GERD-HRDL评分恢复正常[42]。TEMPO是一项随机对照试验(randomized clinical trial,RCT),比较了TIF(N=40)与最大剂量PPIs(N=23)的治疗效果。6月后,90%的TIF组患者可停用PPIs。TIF组与PPIs组食管酸暴露改善率分别为54%、52% (P=0.914)。总体上,TIF在控制GERD症状上优于药物治疗[31]。另一项被美国食品药品监督管理局(Food and Drug Administration,FDA)批准的TIF装置是Medigus超声外科吻合器-MUSETM(Medigusm Omer, Israel)。MUSETM在超声引导下完成胃底折叠,有报道90%的患者可在1年后减量甚至停用PPIs[32]。

一项长期研究显示,TIF治疗10年后,烧心评分、GERD-HRQL评分、反流评分均得到改善。此外,超过86.7%的患者在2年后停止或减半PPIs使用,10年后该比例达到91.7%[43]。最近的一项系统综述与meta分析比较了LNF、TIF、PPIs/安慰剂的治疗效果。TIF在改善GERD-HRQL评分上更优,然而LNF在提高LES压力和降低pH<4时间方面更优[44]。

联合HH修补是TIF的一大技术进展。Janu等人报道了采用HH修补联合TIF治疗99例HH在2-5 cm的患者[45]。结果显示,所有患者均接受腹腔镜下HH修补,随后调整体位进行TIF。在1年后的随访中,GERD-HRQL评分增加了17分(且无烦恼症状)。此外,也未有长期吞咽困难或胀气的报道[45]。

磁性LES增强装置

LINXR 反流控制系统 (Torax Medical, St. Paul, MN) 由若干颗内含磁铁的钛合金珠组成,用于增强LES收缩力。适应人群为无胃部手术史、食管功能正常、HH<3 cm且不肥胖(BMI<35 kg/m2)。腹腔镜下将装置植入食管与迷走神经后干之间的隧道内。相互连接的磁珠放置后可替代胃底折叠术,其大小根据食管直径进行调整。该装置可有效对抗反流,当食管蠕动压大于磁吸引力时则可打开,使得食物通过[46]。

一些研究评估了磁性LES增强装置治疗GERD的安全性及有效性(表2)。一项多中心、单臂研究显示,LINXR置入4年后有效降低了酸暴露总时间(P<0.001)。此外,所有患者(N=23)的GERD-HRQL评分均得到改善,80%的患者(N=20)可停用PPIs。吞咽困难是最常见的术后不适,发生率为43%(N=20)[46]。Lipham等的一项纳入100例患者的研究报道了类似结果,89.4%的患者在5年后可停用PPIs。并发症包括新发的食管炎、吞咽困难[33]。一篇研究回顾了欧美82个中心共计1000例行磁性括约肌增强器置入治疗的患者。术后最常见的不适为吞咽困难和疼痛,围手术期并发症发生率为0.1%(N=1),再入院率为1.3%(N=14),食管腐蚀发生率0.1%(N=1)。高达3.4%(N=36)需要再次手术取出装置,5.6%(N=59)需要食管扩张[34]。另一项研究调研了装置生产商的数据库,自2007年2月至2017年7月共完成了9453例置入。在该研究中,Alicuben等发现12个小型号磁珠装置的食管腐蚀发生率为4.93%(N=18)[47-49]。绝大数发生食管腐蚀的装置首先由内镜下取出,随后再通过腹腔镜取出残余磁珠。置入后1年的食管腐蚀的发生率为0.05%,而到了第4年则达到了0.3%[49]。该研究认为磁性括约肌增强装置致食管腐蚀是罕见的,发生后可以通过微创技术成功处理,且没有长期后遗症。

值得一提的是,Angelchik抗反流装置作为曾经的假体装置,可置于GEJ治疗难治性GERD。Angelchik假体是一个凝胶充填而成的硅胶C形环,1973年最早使用,1979年对其进一步说明。初期结果显示其具有应用价值,并发症率低、住院时间短,预计共放置了3万例。但由于假体环周围会形成致密的纤维化瘢痕,因此带来了许多并发症。最常见的是持续性的吞咽困难,高达70%患者中会出现。此外,胀气、GERD复发、装置移位、食管腐蚀也有发生,约有15%的患者需移除并最终舍弃这一装置[48]。显而易见,LINXR装置发生食管腐蚀以及需要再次取出的发生率明显更低(0.10%~0.15%)。此外,LINX装置引起的炎症反应更局限,在取出时仅需要切除包膜以及适度的黏连[49]。

ARMS

ARMS切除了GEJ的黏膜,继而在贲门处形成瘢痕以减少反流。该技术由井上晴洋教授在一项10例患者的初期研究中首次报道[35]。在最初的2例患者中,因为行全周黏膜切除发生了狭窄,因此之后采用了沿小弯侧使用内镜黏膜切除术(endoscopic mucosal resection,EMR)或内镜黏膜下剥离术(endoscopic submucosal dissection,ESD)作新月形黏膜切除。行透明帽辅助EMR及圈套法或者使用Dual刀行ESD,切除至少3cm的黏膜。保留大弯侧、约镜身直径2倍大小的黏膜,从而形成黏膜瓣。该技术的适应证为难治性GERD、非滑动性HH、合并短段巴雷特食管的患者[49]。研究显示,所有患者均可停用PPIs,pH<4时间从29.1%降至3.1%。全周ARMS术后的狭窄需要多次球囊扩张来治疗。

最近,一项单中心回顾性研究纳入了109例行AMRS的难治性GERD患者(表2)。42%的患者(N=42)在术后2-6月停用PPIs,51%的患者(N=30)在术后1年停药。GERDQ评分在术后2月有明显改善,并且一直维持到术后1年。在该研究中,2名患者出现了术后出血,1例发生穿孔,均予内镜下处理。14.4%患者(N=13)发生狭窄需要行3次以上的扩张。此外,作者发现使用“蝴蝶形”技术将半圆节段之间的小弯侧少部分黏膜保留可有效减少狭窄发生[35]。因此,对于合理选择的GERD患者,AMRS是一项有效、微创、安全的内镜治疗技术[36]。然而,还需要长期研究并纳入不同特征的患者来进一步验证这项技术的价值。

特殊人群:GERD与肥胖

鉴于全球肥胖的高发病率,有必要密切关注这一人群,因为对这部分患者的治疗存在区别。BMI>30 kg/m2的人群,GERD的发病率增高(1.94,1.47-2.57),而且抗反流屏障功能不全的发生率也有所升高[50,51]。Ayazi等发现BMI每增加一个单位,pH<4的总时间增加0.35%,DeMeester综合评分增加1.46%[51]。更为相关的是,BMI>30 kg/m2的患者LARS术后症状及生理复发的发生率高达31%。相比之下,BMI在25–29.9 kg/m2者为8.0%,BMI<25 kg/m2者仅为4.5%[52]。大部分失败的原因是由于包绕的破裂,而非向胸腔内移位,提示内脏脂肪堆积过多使得组织平面扭曲,导致解剖学失败,而腹内压的增加则破坏了缝合和胃底折叠。

虽然有研究表明减重术后体重减轻可持久改善GERD症状,但症状缓解的程度因手术类型不同而有所差异。腹腔镜Roux-en-Y胃旁路术(laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass,LRYGB)、可调节胃束带术、腹腔镜袖状胃切除术(laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy,LSG)的GERD评分改善率分别为56.5%、46%、41%[53]。在超级肥胖患者(BMI >50 kg/m2)中,RYGB术后的GERD缓解率(76.9%)也高于胆胰分流并十二指肠转位术(biliopancreatic diversion and duodenal switch,BPD/DS)(48.6%),BPD/DS组的体重下降更明显[54]。瑞士多中心旁路/袖状胃研究(Swiss Multicenter Bypass or Sleeve Study,SM-BOSS)是一项多中心RCT,研究发现术后5年GERD的缓解率,RYGB组(60.4%)高于LSG组(25%)。此外,LSG组与LRYGB组术后GERD加重的发生率分别为31.8%、6.3%[55]。术后新发的反流上,LSG组为22.9%(N=60),而在LSG联合HH修补组则为0%[56]。值得注意的是,HH修补与否在这些研究中并未加以控制,因此可能对最终结果造成影响。当下的美国代谢减重外科学会(American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery,ASMBS)制定了针对LSG的医疗路径,其中列出了选择性胃镜、上消化道造影、pH/测压检查[57]。其他学者建议将这些作为怀疑或确诊GERD患者的术前常规检查[56,58],并推荐对LSG患者常规行食管裂孔剥离及HH修补[56,57]。

总结

GERD作为西方人群的常见疾病之一,治疗方式多样。虽然PPIs仍是一线治疗方式,但要认识到GERD的治疗应当个体化,并且需要综合患者意愿、症状严重程度、解剖学是否异常等因素,从而制定出最有效的治疗方案。包括内镜与磁装置在内的新兴GERD治疗技术风险低,且显示出不错的效果,因此值得进一步研究其长期疗效。

Acknowledgments

Funding: None.

Footnote

Provenance and Peer Review: This article was commissioned by the Guest Editor (Alfredo Daniel Guerron) for the series “Advanced Laparoscopic Gastric Surgery” published in Digestive Medicine Research. The article has undergone external peer review.

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/dmr-20-128. The series “Advanced Laparoscopic Gastric Surgery” was commissioned by the editorial office without any funding or sponsorship. The authors have no other conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: All authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- Dunlap JJ, Patterson S. Gastroesophageal reflux disease. Gastroenterol Nurs 2019;42:185-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ho KY, Kang JY. Reflux esophagitis patients in Singapore have motor and acid exposure abnormalities similar to patients in the Western hemisphere. Am J Gastroenterol 1999;94:1186-91. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Friedenberg FK, Hanlon A, Vanar V, et al. Trends in gastroesophageal reflux disease as measured by the National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey. Digest Dis Sci 2010;55:1911-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Nau P, Jackson HT, Aryaie A, et al. Surgical management of gastroesophageal reflux disease in the obese patient. Surg Endosc 2020;34:450-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wileman SM, McCann S, Grant AM, et al. Medical versus surgical management for gastro-oesophageal reflux disease (GORD) in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2010;CD003243. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Nabi Z, Reddy DN. Endoscopic management of gastroesophageal reflux disease: revisited. Clin Endosc 2016;49:408-16. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Tack J, Pandolfino JE. Pathophysiology of Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease. Gastroenterology 2018;154:277-88. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Xie C, Li Y, Zhang N, et al. Gastroesophageal flap valve reflected EGJ morphology and correlated to acid reflux. BMC Gastroenterol 2017;17:118. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lee YY, McColl KEL. Pathophysiology of gastroesophageal reflux disease. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol 2013;27:339-51. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gyawali CP, Kahliras PJ, Savarino E, et al. Modern diagnosis of GERD: the Lyon consensus. Gut 2018;67:1351-62. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Katkhouda N. Laparoscopic treatment of gastroesophageal reflux disease—defining a gold standard. Surg Endosc 1995;9:765-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Jobe BA, Richter JE, Hoppo T, et al. Preoperative diagnostic workup before antireflux surgery: an evidence and experience-based consensus of the esophageal diagnostic advisory panel. J Am Coll Surg 2013;217:586-97. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Patti MG. An Evidence-Based Approach to the Treatment of Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease. JAMA Surg 2016;151:73-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Johnson LF, Demeester TR. Twenty-four-hour pH monitoring of the distal esophagus. A quantitative measure of the distal esophagus. Am J Gastroenterol 1974;62:325-32. [PubMed]

- Labenz J, Malfertheiner P. Treatment of uncomplicated reflux disease. World J Gastroenterol 2005;11:4291-99. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kethman W, Hawn M. New approaches to gastroesophageal reflux disease. J Gastrointest Surg 2017;21:1544-52. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Vela MF. Medical treatments of GERD: the old and new. Gastroenterol Clin North Am 2014;43:121-33. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lee L, Ramos-Alvarez I, Ito T, et al. Insights into effects/risks of chronic hypergastrinemia and lifelong PPI treatment in man based on studies of patients with Zollinger-Ellison syndrome. Int J Mol Sci 2019;20:5128. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Brusselaers N, Engstrand L, Lagergren J. Maintenance proton pump inhibition therapy and risk of esophageal cancer. Cancer Epidemiol 2018;53:172-77. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Schein M, Schein H, Wise L. Rudolf Nissen: the man behind the fundoplication. Surgery 1999;125:347-53. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Nissen R. Eine einfache Operation zur Beeinflussung der Refluxeso¨phagitis Schweiz Med Wochenschr 1956;86:590-2. [A simple operation for control of reflux esophagitis]. [PubMed]

- Bammer T, Hinder R, Klaus A, et al. Five- to eight-year outcome of the first laparoscopic Nissen fundoplications. J Gastrointest Surg 2001;5:42-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Dallemagne B, Weerts JM, Jehaes C, et al. Laparoscopic Nissen fundoplication: preliminary report. Surg Laparosc Endosc 1991;1:138-43. [PubMed]

- Blum CA, Adams DB. Who did the first laparoscopic cholecystectomy. J Minim Access Surg 2011;7:165-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lin DC, Chun CL, Triadafilopoulos G. Evaluation and management of patients with symptoms after anti-reflux surgery. Dis Esophagus 2015;28:1-10. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Galmiche JP, Hatlebakk J, Attwood S, et al. Laparoscopic antireflux surgery vs esomeprazole treatment for chronic GERD: the LOTUS randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2011;305:1969-77. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Mahon D, Rhodes M, Decadt B, et al. Randomized clinical trial of laparoscopic Nissen fundoplication compared with proton-pump inhibitors for treatment of chronic gastro-oesophageal reflux. Br J Surg 2005;92:695-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Triadafilopoulos G, DiBaise J, Nostrant TT, et al. The Stretta procedure for the treatment of GERD:6 and 12 month follow-up of the U.S. open label trial. Gastrointest Endosc 2002;55:149-56. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Noar M, Squires P, Noar E, et al. Long-term maintenance effect of radiofrequency energy delivery for refractory GERD: a decade later. Surg Endosc 2014;28:2323-33. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bell RC, Mavrelis PG, Barnes WE, et al. A prospective multicenter registry of patients with chronic gastroesophageal reflux disease receiving transoral incisionless fundoplication. J Am Coll Surg 2012;215:794-809. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Trad KS, Barnes WE, Simoni G, et al. Transoral incisionless fundoplication effective in eliminating GERD symptoms in partial responders to proton pump inhibitor therapy at 6 months: the TEMPO Randomized Clinical Trial. Surg Innov 2015;22:26-40. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Testoni PA, Testoni S, Mazzoleni G, et al. Transoral incisionless fundoplication with an ultrasonic surgical endostapler for the treatment of gastroesophageal reflux disease:12-month outcomes. Endoscopy 2020;52:469-73. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lipham JC, DeMeester TR, Ganz RA, et al. The LINX® reflux management system: confirmed safety and efficacy now at 4 years. Surg Endosc 2012;26:2944-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ganz RA, Edmundowics SA, Taiganides PA, et al. Long-term Outcomes of Patients Receiving a Magnetic Sphincter Augmentation Device for Gastroesophageal Reflux. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2016;14:671-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Inoue H, Ito H, Ikeda H, et al. Anti-reflux mucosectomy for gastroesophageal reflux disease in the absence of hiatus hernia: a pilot study. Ann Gastroenterol 2014;27:346-51. [PubMed]

- Sumi K, Inoue H, Kobayashi Y, et al. Endoscopic treatment of proton pump inhibitor-refractory gastroesophageal reflux disease with anti-reflux mucosectomy: experience of 109 cases. Dig Endosc 2020; Epub ahead of print. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Yeh RW. Triadafilopoulos. Endoscopic antireflux therapy: the Stretta procedure. Thorac Surg Clin 2005;15:395-403. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Leeds S, Reavis K. Endolumenal therapies for gastroesophageal reflux disease. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am 2013;23:41-51. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sowa P, Samarasena JB. Nonablative Radiofrequency Treatment for Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease (STRETTA). Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am 2020;30:253-65. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Perry KA, Banerjee A, Melvin WS. Radiofrequency energy delivery to the lower esophageal sphincter reduces esophageal acid exposure and improves GERD symptoms: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech 2012;22:283-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Fass R, Cahn F, Scotti DJ, et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis of controlled and prospective cohort efficacy studies of endoscopic radiofrequency for treatment of gastroesophageal reflux disease. Surg Endosc 2017;31:4865-82. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Chang KJ, Bell R. Transoral Incisionless Fundoplication. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am 2020;30:267-89. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Testoni PA, Testoni A, Distefano G, et al. Transoral incisionless fundoplication with EsophyX for gastroesophageal reflux disease: clinical efficacy is maintained up to 10 years. Endosc Int Open 2019;7:E647-54. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Richter JE, Kumar A, Lipka S, et al. Efficacy of Laparoscopic Nissen Fundoplication vs Transoral Incisionless Fundoplication or Proton Pump Inhibitors in Patients With Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease: A Systematic Review and Network Meta-analysis. Gastroenterology 2018;154:1298-308.e7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Janu P, Shughoury AB, Venkat K, et al. Laparoscopic hiatal hernia repair followed by transoral incisionless fundoplication with EsophyX device (HH + TIF): efficacy and safety in two community hospitals. Surg Innov 2019;26:675-86. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kuckelman JP, Barron MR, Martin MJ. "The missing LINX" for gastroesophageal reflux disease: Operative techniques video for the Linx magnetic sphincter augmentation procedure. Am J Surg 2017;213:984-87. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lipham JC, Taiganides PA, Louie BE, et al. Safety analysis of first 1000 patients treated with magnetic sphincter augmentation for gastroesophageal reflux disease. Dis Esophagus 2015;28:305-11. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Varshney S, Kelly JJ, Branagan G, et al. Angelchick prosthesis revisited. World J Surg 2002;26:129-33. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Alicuben ET, Bell RCW, Jobe BA, et al. Worldwide experience with erosion of the magnetic sphincter augmentation device. J Gastrointest Surg 2018;22:1442-47. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hampel H, Abraham NS, El-Serag HB. Meta-analysis: obesity and the risk for gastroesophageal reflux disease and its complications. Ann Intern Med 2005;143:199-211. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ayazi S, Hagen JA, Chan LS, et al. Obesity and gastroesophageal reflux: quantifying the association between body mass index, esophageal acid exposure, and lower esophageal sphincter status in a large series of patients with reflux symptoms. J Gastrointest Surg 2009;13:1440-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Perez AR, Moncure AC, Rattner DW. Obesity is a major cause of failure for both abdominal and transthoracic antireflux operations. Gastroenterology 1999;116:A1343.

- Pallati PK, Shaligram A, Shostrom VK, et al. Improvement in gastroesophageal reflux disease symptoms after various bariatric procedures: review of the Bariatric Outcomes Longitudinal Database. Surg Obes Relat Dis 2014;10:502-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Prachand VN, Ward M. ALverdy JC. Duodenal switch provides superior resolution of metabolic comorbidities independent of weight loss in the super-obese (BMI≥50 kg/m2) compared with gastric bypass. J Gastrointest Surg 2010;14:211-20. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Peterli R, Wolnerhanssen BK, Peters T, et al. Effect of Laparoscopic Sleeve Gastrectomy vs Laparoscopic Roux-en-Y Gastric Bypass on Weight Loss in Patients With Morbid Obesity: The SM-BOSS Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA 2018;319:255-65. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Soricelli E, Iossa A, Casella G, et al. Sleeve gastrectomy and crural repair in obese patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease and/or hiatal hernia. Surg Obes Relat Dis 2013;9:356-61. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Telem DA, Gould J, Pesta C, et al. American society of metabolic and bariatric surgery: care pathway for laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy. Surg Obes Relat Dis 2017;13:742-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Rebecchi F, Allaix ME, Giaccone C, et al. Gastroesophageal reflux disease and laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy: a physiopathologic evaluation. Ann Surg 2014;260:909-14. [Crossref] [PubMed]

董弢

硕士,住院医师,南京医科大学附属常州二院胃肠病中心,第一作者于Digestive Endoscopy等期刊发表SCI论文10余篇,Digestive Diseases and Sciences审稿人。(更新时间:2021/9/24)

(本译文仅供学术交流,实际内容请以英文原文为准。)

Cite this article as: Chumakova-Orin M, Castro M, Danois H, Seymour KA. Innovations in gastroesophageal reflux disease interventions—fundoplication, magnets, and endoscopic therapy. Dig Med Res 2020;3:64.