Oncological outcomes for transanal total mesorectal excision

Introduction

Total mesorectal excision (TME) has become the gold standard technique for rectal cancer surgery with curative intent (1). Circumferential resection margin (CRM), distal resection margin (DRM) and quality of TME are the main histopathology metrics directly affecting local recurrence (LR) and cancer-specific survival rates (2).

Advantages in technology and surgical innovation lead to the introduction of minimally invasive techniques including laparoscopic, robotic and, more recently, transanal TME (TaTME).

Obese, male patients with mid-low rectal cancers constitute a well-known challenge to low anterior resection with TME brought into even sharper relief when attempted laparoscopically. There are concerns that such patients with a narrow, radiated pelvis and bulky mesorectum may currently be undergoing sphincter-sparing resections with an involved CRM, a poor quality TME, or even an unnecessary abdominoperineal resection (APR). The concept of TaTME has been proposed to overcome the technical challenges encountered with the transabdominal approaches (open, laparoscopic, robotic) in these more difficult cases.

Recent randomized controlled trials (3-6) and comparative studies (7-8) have reported similar short- and long-term oncological outcomes among open, laparoscopic and robotic approaches. It has been recently claimed that TaTME offers at least three oncological advantages: (I) a longer DRM thanks to the distal transection under direct visual control, (II) a decreased rate of positive CRM, (III) improved quality of TME. However, the oncological outcomes of TaTME compared to those of laparoscopic and robotic TMEs, remain controversial.

The aim of this review was to evaluate TaTME oncological outcomes.

Methods

A review of the literature was performed searching in PubMed, MEDLINE, and Cochrane Library until August 30th, 2019. Two reviewers (CF, AL) independently conducted a search on electronic databases (PubMed, MEDLINE, Cochrane Library) using the following search headings: (“laparoscopic TME” OR “lapTME”) AND (“TaTME”) OR (“robotic rectal surgery”); (“transanal TME”) OR (“taTME”) OR (“Transanal Total mesorectal Excision”); (“transanal” OR “transanal endoscopic microsurgery”) OR (“transanal minimally invasive surgery”) OR (“natural orifice transluminal endoscopic surgery”) OR (“NOTES”) AND (“Tatme oncological outcomes”).

The reference lists provided by the identified articles were additionally hand-searched to prevent article loss by search strategy. This method of cross-references was continued until no further relevant publications were identified. Inclusion criteria were prospective, retrospective, randomized, comparative studies about TaTME for rectal cancer. Exclusion criteria were: abstracts, letters, editorials, technical notes, expert opinions, reviews, meta-analysis, studies reporting benign pathologies, studies in which the outcomes and parameters of patients were not clearly reported, studies in which it was not possible to extract the appropriate data from the published results, overlap between authors and centers in the published literature, studies with inappropriate number of patients (<10); non-English language papers.

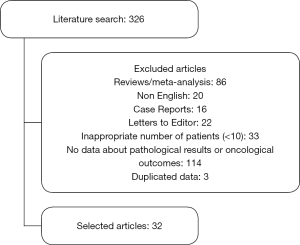

The literature search yielded 326 papers, after the filtering, 32 articles were selected. The process is listed in Figure 1.

Results

Among the 32 selected articles 13 were case series (9-21) and 19 comparative studies (22-40), of these one was a RCT (22). Year of publication ranged from 2014 (22-36) to 2019 (12,23,40). Mean distance of tumor from the anal verge was reported in 17 studies (10-12,17-20,22,26-28,34-38,40) and ranged from 2 (34) to 8 cm (36) for TaTME and from 1.5 (34) to 7 cm (26) in LapTME. Table 1 gives a detailed overview of the selected studies.

Table 1

| Reference | Year | Country | Study design | TaTMe (n) | Lap TME (n) | RobTME (n) | OpTME (n) | Mean distance from anal verge (cm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abdelkader et al. (9) | 2018 | Egypt | Case series | 25 | ||||

| Buchs et al. (10) | 2016 | United Kingdom | Case series | 40 | 3 (0–10) | |||

| Burke et al. (11) | 2016 | United States | Case series | 50 | 4.4 (3.0–5.5) | |||

| De Rosa et al. (12) | 2019 | Italy | Case series | 12 | 6.25 (3.5–10) | |||

| de Lacy et al. (13) | 2018 | Spain | Case series | 186 | ||||

| Hüscher et al. (14) | 2016 | Italy | Cases series | 102 | ||||

| Kang et al. (15) | 2015 | China | Cases series | 20 | ||||

| Lacy et al. (16) | 2015 | Spain | Cases series | 140 | ||||

| Muratore et al. (17) | 2015 | Italy | Cases series | 26 | 4.4 (3–6) | |||

| Park et al. (18) | 2018 | Korea | Cases series | 49 | 6.3±2.2 | |||

| Penna et al. (19) | 2017 | United Kingdom | Cases series | 720 | 3.0 (0–11) | |||

| Rottoli et al. (20) | 2015 | United Kingdom | Cases series | 11 | 5 (2–7) | |||

| Veltcamp et al. (21) | 2016 | Netherlands | Cases series | 80 | ||||

| Denost et al. (22) | 2014 | France | Comparative RCT | 50 | 4 (2–6) | |||

| 50 | 4 (2–6) | |||||||

| Detering et al. (23) | 2019 | Netherlands | Comparative | 396 | 396 | |||

| Fernández-Hevia et al. (24) | 2015 | Spain | Comparative | 37 | 37 | |||

| Kanso et al. (25) | 2015 | France | Comparative | 51 | 34 | |||

| Law et al. (26) | 2018 | Hong Kong | Comparative | 40 | 5 (2–10) | |||

| 40 | 7 (2–15) | |||||||

| Lee L et al. (27) | 2018 | Multicenter | Comparative | 226 | 370 | 5.6 (2.5) | ||

| Lee KY et al. (28) | 2018 | Korea | Comparative | 26 | 6.1±1.63 | |||

| 36 | 5.2±1.99 | |||||||

| Lelong et al. (29) | 2016 | France | Comparative | 34 | 38 | |||

| Mege et al. (30) | 2018 | United States | Comparative | 23 | 34 | |||

| Perdawood et al. (31) | 2018 | Denmark | Comparative | 100 | 100 | 100 | ||

| Perez et al. (32) | 2017 | Germany | Comparative | 55 | 60 | |||

| Persiani et al. (33) | 2018 | Italy | Comparative | 48 | 57 | |||

| Roodbeen et al. (34) | 2018 | Multicenter | Comparative | 41 | 2.0 (0.0–4.0) | |||

| 41 | 1.5 (0.0–3.0) | |||||||

| Rubinkiewicz et al. (35) | 2018 | Poland | Comparative | 35 | 2.9±1.17 | |||

| 35 | 3.19±1.47 | |||||||

| Velthuis et al. (36) | 2014 | Netherlands | Comparative | 25 | 8 | |||

| 25 | 6 | |||||||

| Caycedo-Marulanda et al. (37) | 2018 | Canada | Comparative | 43 | 6.80±2.09 | |||

| Chang et al. (38) | 2018 | Taiwan | Comparative | 23 | 4.3±1.4 | |||

| 23 | 5.9±1.1 | |||||||

| Chen CC et al. (39) | 2016 | Taiwan | Comparative | 50 | 100 | |||

| Chen YT et al. (40) | 2019 | Taiwan | Comparative | 39 | 4.3±1.4 | |||

| 64 | 5.8±1.2 | |||||||

| 23 | 5.6±1.3 |

TME, total mesorectal excision; TaTME, transanal TME; LapTME, laparoscopic TME. RobTME, robotic TME; OpTME, open TME.

Number of harvested nodes

Twenty-six out of 31 studies reported the mean number of harvested nodes which ranged from 10.7 (28) to 26.45 (26) in TaTME; from 11 (28) to 26.69 (26) in laparoscopic TME (LapTME) and from 13 (17) to 16.8 (18) in robotic TME (RobTME). The mean number of harvested nodes after open TME (OpTME) was reported in 1 study and was 23.5±8.2 (7).

One (31) of the 16 comparatives studies (22,24-34,36,38-40) reported statistically significant difference in number of harvested nodes beetwen Ta- and OpTME but no difference was reported when Ta- and LapTME were compoared. Table 2 shows the results in details.

Table 2

| Reference | Pts | Surgical technique | Harvested nodes | Distal margin distance (cm) | CRM + (%) | CRM (mm) | Complete TME | Nearly complete TME | Incomplete TME |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abdelkader et al. (9) | 25 | TaTME | 1.9±1.1 | 2 (8) | 22 (88) | 2 (8) | 1 (4) | ||

| Buchs et al. (10) | 40 | TaTME | 20±9.7 | 2.69±2.22 | 2 (5) | 10.8±9.5 | |||

| Burke et al. (11) | 50 | TaTME | 18.0 (12.0–23.8) | 1.0 (0.5–1.7) | 2 (4) | 7.0 (2.5–15.0) | 36 (72) | 13 (26) | 1 (2) |

| De Rosa et al. (12) | 12 | TaTME | 13.6±6.6 | 2.08±1.42 | 16.1±7.6 | 12 (100) | 0 | 0 | |

| de Lacy et al. (13) | 186 | TaTME | 14.0 | 2.1 | 7 (10.1) | 15.4 | 178 (95.7) | 3 (1.6) | 2 (1.1) |

| Hüscher et al. (14) | 102 | TaTME | 20±11.7 | 3.71±2.85 | 37.1±28.5 | 99 (97.1) | 3 (2.9) | ||

| Kang et al. (15) | 20 | TaTME | 1.0 (0.5–2.5) | 0 (0) | 12 (3–19) | 18 (90) | 2 (10%) | 0 | |

| Lacy et al. (16) | 140 | TaTME | 14.7±6.8 | 9 (6.4) | 22±4 | 136 (97.1) | 3 | 1 | |

| Muratore et al. (17) | 26 | TaTME | 1.9 | 11.1 | 23 (88.4) | ||||

| Park et al. (18) | 49 | TaTME | 19 (8–42) | 2.4±0.19 | 4 (8.2) | 35 (71.4) | 12 (24.5) | 2 (4.1) | |

| Penna et al. (19) | 720 | TaTME | 16.5±9.2 | 1.9±1.43 | 14 (2.4) | 9.19±8.6 | |||

| Rottoli et al. (20) | 11 | TaTME | 21.7 (11–50) | 1 (0.5–2.0) | 5 (1–20) | 0 | |||

| Veltcamp et al. (21) | 80 | TaTME | 14 (6–30) | Positive DRM: 0% | 2 (2.5)£ | 71 (88) | 7 (9) | 2 (3) | |

| Denost et al. (22) | 50 | TaTME | 17 (2–30) | 1 (0–3)§ | 2 (4) | 7 (0–20) | 35 (70) | 9 (18) | 6 (12) |

| 50 | LapTME | 17 (9–40) | 1 (0.1–3)§ | 9 (18) | 5 (0–20) | 31 (62) | 13 (26) | 6 (12) | |

| Detering et al. (23) | 396 | TaTME | 17 (4.3) | ||||||

| 396 | LapTME | 16 (4.0) | |||||||

| Fernández-Hevia et al. (24) | 37 | TaTME | 14.3±6 | 2.8±1.8 | 0 | 11±0.6 | 35 (95) | 2 (5) | 0 |

| 37 | LaTME | 14.7±6 | 1.7±1.3 | 0 | 12±0.9 | 34 (92) | 2 (5) | 1 (3) | |

| Kanso et al. (25) | 51 | TaTME | 15±8 | 1.2±0.9^ | 5 (10) | 7±6 | |||

| 34 | LapTME | 13±7 | 1.8±1.5^ | 3 (9) | 7±6 | ||||

| Law et al. (26) | 40 | TaTME | 13 | 2 (0.5–5) | 0 (0) | ||||

| 40 | RobTME | 13 | 2 (0.5–6) | 2 (5) | |||||

| Lee L et al. (27) | 226 | TaTME | 16.1 | 1.69! | 12 (6.3) | 209 (92.5) | 15 (6.6) | 2 (0.9) | |

| 370 | RobTME | 16.8 | 1.51! | 21 (6.2) | 356 (95.4) | 14 (3.8) | 3 (0.8) | ||

| Lee KY et al. (28) | 21 | TaTME | 10.7±6.28 | 2.2±1.28 | 1 (4.8) | 19 (90.5) | 2 (94.5) | 0 | |

| 24 | RobTME | 13.6±6.29 | 1.9±1.06 | 2 (8.3) | 24 (100) | 0 | 0 | ||

| Lelong et al. (29) | 34 | TaTME | 14 (6–34) | 2 (5.8) | 19 (55.8) | 15 | 0 | ||

| 38 | LapTME | 12 (4–25) | 4 (10.5) | 20 (52.6) | 16 | 2 | |||

| Mege et al. (30) | 34 | TaTME | 14±10 | Positive DRM TaTME 1 (3%) vs. LapTME 1 (3%) P=1 | 4 (12) | 18 (53) | 9 (27) | 7 (21) | |

| 34 | LapTME | 14±8 | 2 (6) | 27 (79) | 3 (9) | 4 (12) | |||

| Perdawood et al. (31) | 100 | TaTME | 22.32±8.70# | 2.22±1.27” | 7 (7) | 8.99±7.21 | 58 (58)& | 28 (28)& | 14 (14)& |

| 100 | LapTME | 21.75±10.98# | 2.40±1.51” | 13 (13) | 9.44±7.86 | 68 (68)& | 12 (12)& | 20 (20)& | |

| 100 | OpTME | 17.92±9.29# | 3.47±2.35” | 10 (10) | 9.57±7.49 | 68 (68)& | 15 (15)& | 17 (17)& | |

| Perez et al. (32) | 55 | TaTME | 15 (8–55) | 1.9 (0.8–3) | 12 (5–20) | 50 (91) | 5 (9) | 0 | |

| 60 | RobTME | 15 (7–30) | 3.1 (1.9–4.5) | 19 (12–49) | 53 (88) | 7 (12) | 0 | ||

| Persiani et al. (33) | 48 | TaTME | 12 (3–26) | 2.5 (0.5–6) | 0 | 40 (87) | 4 (8.7) | 2 (4.3) | |

| 57 | LapTME | 11 (3–26) | 1.5 (0.5–4) | 0 | 39 (84.8) | 5 (10.9) | 2 (4.3) | ||

| Roodbeen et al. (34)€ | 41 | TaTME | 18 (13–26) | 2 (1–4) | 3 (7) | 10 (4.2–12) | 38 (92.7) | ||

| 41 | LapTME | 14 (11–24) | 2 (0.98–4.13) | 2 (4.8) | 5 (3–10) | 21 (84.0) | |||

| Rubinkiewicz et al. (35) | 35 | TaTME | Positive DRM 0 TaTME vs. 1 (2.8%) LapTME | 1 (2.8) | 31 (89) | 4 (11) | 0 (0) | ||

| 35 | LapTME | 0 | 29 (83) | 6 (17) | 0 (0) | ||||

| Velthuis et al. (36) | 25 | TaTME | 14 (7–24) | 2.3 (0.5–8) | 1 (4)£ | 13 (1.5–3) | 24 (96) | 1 (4%) | 0 |

| 25 | LapTME | 13 (1–36) | 2.5 (0–5.5) | 2 (8)£ | 12 (0–2.5) | 18 (72) | 2 (8%) | 5 (20) | |

| Caycedo-Marulanda et al. (37) | 43 | TaTME | 24.81±9.90 | 1 (2.33) | 36 (83.72) | 7 (16.28) | 0 | ||

| Chang et al. (38) | 23 | TaTME | 22.8±10.8 | 1.35±1.05 | 0 (0) | ||||

| 23 | LapTME | 19.5±8.6 | 1.55±1.05 | 4 (7) | |||||

| Chen CC et al. (39) | 50 | TaTME | 16.7±7.8 | 2.4±1.2 | 2 (4) | 11.8±7.5 | |||

| 100 | LapTME | 17.4±8.9 | 1.5±0.9 | 10 (10) | 11.1±7.7 | ||||

| Chen YT et al. (40) | 39 | TaTME | 20.8±9.0 | 1.6±1.4 | 0* | ||||

| 64 | LapTME | 18.8±8.1 | 1.9±1.3 | 5 (7.8)* | |||||

| 23 | OpenTME | 23.5±8.2 | 1.6±0.9 | 3 (13)* |

*, TaTME vs. LapTME P=0.08; TaTME vs. OpTME P<0.01; Lap TME vs. OpTME P=0.2; §, positive DRM TaTME 1 (2%) vs. LapTME 4 (8%) P=0.362; ^, positive DRM TaTME 4 (8%) vs. LapTME 0 P=0.25; !, positive DRM TaTME 4 (1.8%) vs. RobTME 1 (0.3%) P=0.051; #, TaTME vs. LapTME P=0.889; TaTME vs. OpTME P=0.003; LapTME vs. OpTME P=0.018; “, TaTME vs. LapTME P=0.995; TaTME vs. OpTME P<0.065; LapTME vs. OpTME P=0.052; positive DRM TaTME 0, LapTME 1, OpTME 1 P=0.604; &, TaTME vs. LapTME P=0.016; TaTME vs. OpTME P=0.082; LapTME vs. OpTME P=0.750; €, positive DRM TaTME 0 vs. Lap TME 3 (7%) P=0.241; £, positive CRM <2 mm. TME, total mesorectal excision; TaTME, transanal TME; LapTME, laparoscopic TME. RobTME, robotic TME; OpTME, open TME.

DRM

Twenty-five (9-15,17-20,22,24-28,31-34,36,38-40) out of 31 studies reported the DRM which ranged from 1 cm (3,10,14,29) to 2.8 cm (24) in TaTME. The mean length of DRM after LapTME was available in 10 (22,24,25,31,33-36,38-40) studies and ranged from 1 cm (10) to 2.5 cm (36). The mean length of DRM after RobTME was reported in 4 (26-28,32) articles and ranged from 1.5 cm (27) to 3.1 cm (32). DRM after OpTME was reported in 2 studies (31,40) and was 1.6 and 3.47 cm (31,40).

Five (6,25,27,31,32) out 18 (24,31-33,39) comparative studies reported statistically significant difference in mean length of DRM. Three studies reported significantly longer mean DRM after TaTME vs. Lap TME (6,25,27). One study (32) reported longer DRM after Rob TME vs. TaTME. Perdawood et al. (31) reported longer DRM when TaTME or LapTME where compared to OpTME, but no difference was reported between TaTME and LapTME. Six comparative studies (22,25,27,30,31,34) reported the DRM involvement rate which ranged from 0% to 8% in the TaTME and LapTME cases, DRM was involved in 0.3% of RobTME in the only study reporting this data (27). No statistically significant difference was reported among studies in DRM involvement rates. Table 2 shows the results in details.

CRM

CRM involvement after TaTME surgery were reported in 27 studies (Table 2). And ranged from 0% (15,24,26,33,38,40) to 12% (30) after TaTME, from 0% (24,33,35) to 13% (31) in 7 studies (22-25,29-31) reporting LapTME, from 5% (26) to 8.3% (28) in 3 studies reporting RobTME (26-28) and was 10% (31) and 13% (40) in 2 studies reporting OpTME (31,40). Three studies reported significantly lower CRM involvement rates in TaTME vs. LapTME (22,38,40) or OpTME (40). Among these 3 studies (22,38,40), one was a RCT (22) comparing the transanal and laparoscopic approach. The cut-off to define a positive CRM was 1 mm in 25 studies (9-11,13,15,16,18,19,22-31,33-35,37-40) and 2 mm in 2 studies (21,36). Eighteen studies (10-17,19,20,22,24,25,31,32,34,36,39) reported the CRM width in mm, of these 8 were comparative (22,24,25,31,32,34,36,39). CRM width ranged from 5 mm (20) to 37.1 mm (14) in TaTME, from 5 (22,34) to 12 mm (24,36) in LapTME. One study reported the width of CRM in the OpTME (31) and another in the RobTME (32). This last study (32) reported a statistically significant wider CRM in the RobTME vs. the TaTME group. Table 2 shows the results in details.

Quality of TME

Quality of TME according to Quirke (41) was evaluated in 23 studies (9,11-18,21,22,24,27-37) [12 comparative (22,24,27-36)]. Complete quality of specimen ranged from 53% (30) to 100% (12) after TaTME, from 52.6% (29) to 92% (24) in the 9 studies evaluating LapTME (22,24,29-31,33-37], from 88% (32) to 100% (28) in the 3 studies reporting RobTME (27,28,32) and was 68% in one study reporting OpTME (31). Incomplete quality of TME ranged from 0% (12,15,20,24,28,29,32,35-37] to 21% (30) in TaTME, from 0% (28,35) to 20% (31,36) in LapTME and was 0% in the 2 studies reporting RobTME (28,32) and 17% in one study reporting OpTME (31). Two (31,36) out of the 12 comparative (22,24,27-36) studies reported a statistically significant higher rate of complete TME with TaTME vs. LapTME. Table 2 shows the results in details.

Long-term survival

Eight studies (9,10,11,16,21,25,27,40) reported long term follow-up data, of these 3 were comparative (25,27,40). Follow-up time was reported in median (15.1–39 months) (11,25,27) or mean (15–28.6 months) (9,10,16). LR, DFS and OS rates after TaTME ranged from 0% (40) to 4.8% (27), from 63% (25) to 90.8% (16) and from 92.5% (10) to 100% (25) respectively. Chen et al. (40) reported a statistically higher DFS when TaTME and LapTME were compared to OpTME (P=0.01), no difference in DFS was reported when taTME was compared to LapTME (P=0.7). Table 3 shows the results in details.

Table 3

| Reference | Patients | Surg technique | Follow-up (months) | Local recurrence (%) | DFS | OS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abdelkader et al. (9) | 25 | TaTME | 28.6±5.9 (7–36) mean | 1 (4) | 22 (88) | |

| Buchs et al. (10) | 40 | TaTME | 6.5 mean | 34 (85) | 37 (92.5) | |

| Burke et al. (11) | 50 | TaTME | 15.1 (7–23.7) Median | 2 (4) | 41 (82)£ | |

| Lacy et al. (16) | 140 | TaTME | 15±9.1 mean | 1 (0.8) | 119 (90.8) | 136 (97.1) |

| Veltcamp et al. (21) | 80 | TaTME | 30 | 2 (2.5) | ||

| Kanso et al. (25) | 51 | TaTME | 39 (0–85) | 32 (63) | 51 (100) | |

| 34 | LapTME | Median | 21 (62) | 32 (93) | ||

| Lee et al. (27) | 21 | TaTME | 20.1 | 1 (4.8) | ||

| 24 | RobTME | 22 median | 0 (0) | |||

| Chen YT et al. (40) | 39 | TaTME | 24 | 0 (0) | 2 (90)* | 2 (97) |

| 64 | LapTME | 3 (4.7) | 2 (91)* | 2 (89) | ||

| 23 | OpenTME | 2 (8.7) | 2 (65)* | 2 (89) |

*, TaTME vs. LapTME P=0.7; TaTME vs. Op TME P=0.01; LapTME vs. OpTME P=0.01; £, 2 patients already metastatic at diagnosis. TME, total mesorectal excision; TaTME, transanal TME; LapTME, laparoscopic TME.

Discussion

The gold standard treatment for mid-low rectal cancers is TME, which has been elucidated to optimize locoregional clearance (1) and to decrease LR rates (42).

Laparoscopic and robotic TME represent a leap forward in the treatment of rectal neoplasms, providing improved short-term and analogous long-term outcomes (3-8,43). However, performing an anterior rectal resection with a good quality TME is technically challenging, particularly with the laparoscopic approach, due to the tapering of the distal mesorectum and inadequate identification of the neurovascular bundle, and mainly because of the limited operative field leading to a difficult view and difficult placement of endoscopic staplers and mobilization in the deep pelvis. Aforementioned factors in combination with suboptimal anastomotic techniques evoke insufficiency of DRM, incompleteness of mesorectum and CRM involvement, with consequent LR. Previous RCTs (3,44) found a high involvement of CRM rate (7–12.1%) in laparoscopic TME. The ROLARR trial (8) found no statistically significant oncological or clinical advantage of RobTME over LapTME with positive CRM rates of 5.1% and 6.3% respectively. The “bottom-up” approach of TaTME was pioneered to minimize the limits of the “up-to-down” approaches. In fact, TaTME helps to clearly expose the anatomical plane and accurately determine the resection margin in a narrow pelvis, as well as a more direct approach to the most problematic aspects of the distal rectal dissection, thus in turn producing better perioperative results, enhanced oncological quality as well as superior nerve-sparing (45,46).

This review was focused on the quality of TME, DRM and CRM as they are the measures of the TME quality and are deemed as major predictive factors for rectal resections affecting LR and survival (1,41,47). TaTME resulted to provide good oncologic outcomes and seems to be associated with a lower rate of CRM involvement and TME incompleteness when compared to the abdominal approaches (laparoscopic, robotic, open). These results were also reported by two recent meta-analysis comparing one Ta- and LapTME (48) and the other Ta-, Rob- and OpTME (49). Ma et al. (50) in their systematic review and meta-analysis reported longer CRM, less positive CRM rates and a higher rate of complete specimens when TaTME was compared with LapTME. Another meta-analysis analysing Ta- and RobTME (51) reported lower pooled CRM involvement rates for TaTME, although this result was not statistically nor clinically significant. Accordingly, the only RCT (22) comparing Ta- and LapTME reported a significantly lower CRM involvement rate with the bottom-up approach.

It is undeniable that the core value of TaTME lies in achieving an adequate DRM as the rectal transection is under direct visual control. Nonetheless, there was no significant difference among studies in terms of DRM as reported also by a recent meta-analysis (51). Surprisingly, one study (32) reported significantly lower DRM and CRM in the TaTME group when compared to the robotic approach although there were no differences among the two groups in tumor size and site, neoadjuvant therapy or Quirke’s mesorectal grading. However, a possible institutional bias with different pathological assessment of the specimens may have affected the results. For this reason, result pertaining DRM should be interpreted cautiously as it is important to point out the heterogeneity of the published studies in terms of tumor size and tumor stage and mainly of tumor location (48,50,51).

A study by Perdawood et al. (52) aiming to compare 29 TaTME to 29 LapTME cases with defects in the retrieved specimen reported a significantly longer DRM in the TaTME group (33.45+14.5 vs. 25.41+11.16; P=0.048). Interestingly, the ratio of defects below the peritoneal reflection was significantly lower in the TaTME group suggesting that TaTME has the potential to improve rectal cancer surgery through improvement of dissection in the lower rectum.

It is important to note that most of the reported studies included the surgeon’s learning curve and despite this, results were very promising.

Most studies have reported only short-term outcomes, which reflects the novelity of TaTME. Whether this new approach has similar oncological outcomes in terms of LR, DFS and cancer specific survival will require further studies in prospective trials that compare TaTME with laparoscopic or robotic TME over substantial follow-up period.

As TaTME is adopted increasingly by surgeons, patients’ selection criteria will be crucial to continue to animate the debate. Hopefully, the TaTME international registry as well as COLOR III RCT (53) with its strict selection criteria will give definitive answers on short- and long-term oncologic outcomes after TaTME (vs. lapTME).

Conclusions

TaTME is an oncologically safe and effective technique, resulting in at least comparable oncologic outcomes when compared to the abdominal approaches. Standardization of surgical technique, implementation in daily practice as well as strict selection criteria are required to further clarify the role of TatME in the treatment of rectal cancer. Hopefully, the COLOR III multicenter RCTs will shed a light on short- and long-term oncologic outcomes after TaTME.

Acknowledgments

Funding: None.

Footnote

Provenance and Peer Review: This article was commissioned by the Guest Editors (Janindra Warusavitarne and Roel Hompes) for the series “TaTME” published in Digestive Medicine Research. The article has undergone external peer review.

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/dmr.2019.12.01). The series “TaTME” was commissioned by the editorial office without any funding or sponsorship. AS acted as teacher/consultant/speaker for Ethicon and Takeda. The authors have no other conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- Heald RJ, Husband EM, Ryall RD. The mesorectum in rectal cancer surgery: the clue to pelvic recurrence? Br J Surg 1982;69:613-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Birbeck KF, Macklin CP, Tiffin NJ, et al. Rates of circumferential resection margin involvement vary between surgeons and predict outcomes in rectal cancer surgery. Ann Surg 2002;235:449-57. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- van der Pas MH, Haglind E, Cuesta MA, et al. Laparoscopic versus open surgery for rectal cancer (COLOR II): short-term outcomes of a randomised, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol 2013;14:210-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Jeong SY, Park JW, Nam BH, et al. Open versus laparoscopic surgery for mid-rectal or low-rectal cancer after neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy (COREAN trial): survival outcomes of an open-label, non-inferiority, randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol 2014;15:767-74. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kang SB, Park JW, Jeong SY, et al. Open versus laparoscopic surgery for mid or low rectal cancer after neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy (COREAN trial): short-term outcomes of an open-label randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol 2010;11:637-45. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Jayne DG, Thorpe HC, Copeland J, et al. Five-year follow-up of the Medical Research Council CLASICC trial of laparoscopically assisted versus open surgery for colorectal cancer. Br J Surg 2010;97:1638-45. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Park EJ, Cho MS, Baek SJ, et al. Long-term oncologic outcomes of robotic low anterior resection for rectal cancer: a comparative study with laparoscopic surgery. Ann Surg 2015;261:129-37. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Jayne D, Pigazzi A, Marshall H, et al. Robotic-assisted surgery compared with laparoscopic resection surgery for rectal cancer: the ROLARR RCT. Efficacy and Mechanism Evaluation 2019. doi:

10.3310/eme06100 . - Abdelkader AM, Zidan AM, Younis MT, et al. Transanal total mesorectal excision for the treatment of carcinoma in the Middle or Lower Third Rectum: the Technical Feasibility of the Procedure, Pathological Results, and Clinical Outcome. Indian J Surg Oncol 2018;9:442-51. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Buchs NC, Wynn G, Austin R, et al. A two-centre experience of transanal total mesorectal excision. Colorectal Dis 2016;18:1154-61. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Burke JP, Martin-Perez B, Khan A, et al. Transanal total mesorectal excision for rectal cancer: early outcomes in 50 consecutive patients. Colorectal Dis 2016;18:570-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- De Rosa M, Rondelli F, Boni M, et al. Transanal total mesorectal excision (TaTME): single-centre early experience in a selected population. Updates Surg 2019;71:157-63. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- de Lacy FB, van Laarhoven JJEM, Pena R, et al. Transanal total mesorectal excision: pathological results of 186 patients with mid and low rectal cancer. Surg Endosc 2018;32:2442-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hüscher CG, Tierno SM, Romeo V, et al. Technologies, technical steps, and early postoperative results of transanal TME. Minim Invasive Ther Allied Technol 2016;25:247-56. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kang L, Chen WH, Luo SL, et al. Transanal total mesorectal excision for rectal cancer: a preliminary report. Surg Endosc 2016;30:2552-62. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lacy AM, Tasende MM, Delgado S, et al. Transanal Total Mesorectal Excision for Rectal Cancer: Outcomes after 140 Patients. J Am Coll Surg 2015;221:415-23. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Muratore A, Mellano A, Marsanic P, et al. Transanal total mesorectal excision (taTME) for cancer located in the lower rectum: short- and mid-term results. Eur J Surg Oncol 2015;41:478-83. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Park SC, Sohn DK, Kim MJ, et al. Phase II Clinical Trial to Evaluate the Efficacy of Transanal Endoscopic Total Mesorectal Excision for Rectal Cancer. Dis Colon Rectum 2018;61:554-60. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Penna M, Hompes R, Arnold S, et al. Transanal Total Mesorectal Excision: International Registry Results of the First 720 Cases. Ann Surg 2017;266:111-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Rottoli M, Hanna L, Kukreja N, et al. Is transanal total mesorectal excision a reproducible and oncologically adequate technique? A pilot study in a single center. Int J Colorectal Dis 2016;31:359-63. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Veltcamp Helbach M, Deijen CL, Velthuis S, et al. Transanal total mesorectal excision for rectal carcinoma: short-term outcomes and experience after 80 cases. Surg Endosc 2016;30:464-70. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Denost Q, Adam JP, Rullier A, et al. Perineal transanal approach: a new standard for laparoscopic sphincter-saving resection in low rectal cancer, a randomized trial. Ann Surg 2014;260:993-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Detering R, Roodbeen SX, van Oostendorp SE, et al. Three-Year Nationwide Experience with Transanal Total Mesorectal Excision for Rectal Cancer in the Netherlands: A Propensity Score-Matched Comparison with Conventional Laparoscopic Total Mesorectal Excision. J Am Coll Surg 2019;228:235-44.e1. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Fernández-Hevia M, Delgado S, Castells A, et al. Transanal total mesorectal excision in rectal cancer: short-term outcomes in comparison with laparoscopic surgery. Ann Surg 2015;261:221-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kanso F, Maggiori L, Debove C, et al. Perineal or Abdominal Approach First During Intersphincteric Resection for Low Rectal Cancer: Which Is the Best Strategy? Dis Colon Rectum 2015;58:637-44. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Law WL, Foo DCC. Comparison of early experience of robotic and transanal total mesorectal excision using propensity score matching. Surg Endosc 2019;33:757-63. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lee L, de Lacy B, Gomez Ruiz M, et al. A Multicenter Matched Comparison of Transanal and Robotic Total Mesorectal Excision for Mid and Low-rectal Adenocarcinoma. Ann Surg 2019;270:1110-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lee KY, Shin JK, Park YA, et al. Transanal Endoscopic and Transabdominal Robotic Total Mesorectal Excision for Mid-to-Low Rectal Cancer: Comparison of Short-term Postoperative and Oncologic Outcomes by Using a Case-Matched Analysis. Ann Coloproctol 2018;34:29-35. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lelong B, Meillat H, Zemmour C, et al. Short- and Mid-Term Outcomes after Endoscopic Transanal or Laparoscopic Transabdominal Total Mesorectal Excision for Low Rectal Cancer: A Single Institutional Case-Control Study. J Am Coll Surg 2017;224:917-25. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Mege D, Hain E, Lakkis Z, et al. Is trans-anal total mesorectal excision really safe and better than laparoscopic total mesorectal excision with a perineal approach first in patients with low rectal cancer? A learning curve with case-matched study in 68 patients. Colorectal Dis 2018;20:O143-51. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Perdawood SK, Thinggaard BS, Bjoern MX. Effect of transanal total mesorectal excision for rectal cancer: comparison of short-term outcomes with laparoscopic and oper surgeries. Surg Endosc 2018;32:2312-21. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Perez D, Melling N, Biebl M, et al. Robotic low anterior resection versus transanal total mesorectal excision in rectal cancer: A comparison of 115 cases. Eur J Surg Oncol 2018;44:237-42. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Persiani R, Biondi A, Pennestrì F, et al. Transanal Total Mesorectal Excision vs Laparoscopic Total Mesorectal Excision in the Treatment of Low and Middle Rectal Cancer: A Propensity Score Matching Analysis. Dis Colon Rectum 2018;61:809-16. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Roodbeen SX, Penna M, Mackenzie H, et al. Transanal total mesorectal excision (TaTME) versus laparoscopic TME for MRI-defined low rectal cancer: a propensity score-matched analysis of oncological outcomes. Surg Endosc 2019;33:2459-67. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Rubinkiewicz M, Nowakowski M, Wierdak M, et al. Transanal total mesorectal excision for low rectal cancer: a case-matched study comparing TaTME versus standard laparoscopic TME. Cancer Manag Res 2018;10:5239-45. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Velthuis S, Nieuwenhuis DH, Ruijter TE, et al. Transanal versus traditional laparoscopic total mesorectal excision for rectal carcinoma. Surg Endosc 2014;28:3494-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Caycedo-Marulanda A, Ma G, Jiang HY. Transanal total mesorectal excision (taTME) in a single-surgeon setting: refinements of the technique during the learning phase. Tech Coloproctol 2018;22:433-43. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Chang TC, Kiu KT. Transanal Total Mesorectal Excision in Lower Rectal Cancer: Comparison of Short-Term Outcomes with Conventional Laparoscopic Total Mesorectal Excision. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A 2018;28:365-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Chen CC, Lai YL, Jiang JK, et al. Transanal Total Mesorectal Excision Versus Laparoscopic Surgery for Rectal Cancer Receiving Neoadjuvant Chemoradiation: A Matched Case-Control Study. Ann Surg Oncol 2016;23:1169-76. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Chen YT, Kiu KT, Yen MH, et al. Comparison of the short-term outcomes in lower rectal cancer using three different surgical techniques: Transanal total mesorectal excision (TME), laparoscopic TME, and open TME. Asian J Surg 2019;42:674-80. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Quirke P, Steele R, Monson J, et al. Effect of the plane of surgery achieved on local recurrence in patients with operable rectal cancer: a prospective study using data from the MRC CR07 and NCIC-CTG CO16 randomised clinical trial. Lancet 2009;373:821-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- van Gijn W, Marijnen CA, Nagtegaal ID, et al. Preoperative radiotherapy combined with total mesorectal excision for resectable rectal cancer: 12-year follow-up of the multicentre, randomised controlled TME trial. Lancet Oncol 2011;12:575-82. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bonjer HJ, Deijen CL, Abis GA, et al. A randomized trial of laparoscopic versus open surgery for rectal cancer. N Engl J Med 2015;372:1324-32. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Fleshman J, Branda M, Sargent DJ, et al. Effect of laparoscopic assisted resection vs open resection of stage II or III rectal cancer on pathologic outcomes: the ACOSOG Z6051 randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2015;314:1346-55. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Heald RJ. A new solution to some old problems: transanal TME. Tech Coloproctol 2013;17:257-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Aigner F, Hörmann R, Fritsch H, et al. Anatomical considerations for transanal minimal-invasive surgery: the caudal to cephalic approach. Colorectal Dis 2015;17:O47-53. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Nagtegaal ID, van de Velde CJ, van der Worp E, et al. Macroscopic evaluation of rectal cancer resection specimen: clinical significance of the pathologist in quality control. J Clin Oncol 2002;20:1729-34. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Zhang X, Gao Y, Dai X, et al. Short- and long-term outcomes of transanal versus laparoscopic total mesorectal excision for mid-to-low rectal cancer: a meta-analysis. Surg Endosc 2019;33:972-85. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Simillis C, Lal N, Thoukididou SN, et al. Open versus laparoscopic versus robotic versus transanal mesorectal excision for rectal cancer. A systematic review and network meta-analysis. Ann Surg 2019;270:59-68. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ma B, Gao P, Song Y, et al. Transanal total mesorectal excision (TaTME) for rectal cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis of oncological and perioperative outcomes compared with laparoscopic total mesorectal excision. BMC Cancer 2016;16:380. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gachabayov M, Tulina I, Bergamaschi R, et al. Does transanal mesorectal excision of rectal cancer improvce histopathology metrics and/or complication rates? A meta analysis. Surg Oncol 2019;30:47-51. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Perdawood SK, Warnecke M, Bjoern MX, et al. The pattern of defects in mesorectal specimens: is there a difference between transanal and laparoscopic approaches? Scand J Surg 2019;108:49-54. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Deijen CL, Velthuis S, Tsai A, et al. COLOR III: a multicenter randomised clinical trial comparing transanal TME versus laparoscopic TME for mid and low rectal cancer. Surg Endosc 2016;30:3210-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

Cite this article as: Foppa C, Luberto A, Spinelli A. Oncological outcomes for transanal total mesorectal excision. Dig Med Res 2020;3:17.